Hannah Beachler

Hannah Beachler made a name for herself designing critically-praised independent films like Creed, Fruitvale Station, and the Best Picture-winning Moonlight. Now she oversees $30 million art department budgets for films like the blockbuster Black Panther, for which she won an Academy Award. She’s staying busy during the coronavirus epidemic and will soon be prepping Black Panther 2…

AS: Is all film work shut down for you because of coronavirus?

HB: I was on location in Detroit with Steven Soderbergh and the production said, We’re on hiatus. We’re going to be back in a couple weeks. So we just walked away. We didn’t wrap anything. We left our offices as-is, warehouses, everything. But now we’re finally getting the call to wrap out. And to me that kind of indicates that we’re not coming back anytime soon.

AS: Do you have any thoughts about how the industry might start back up?

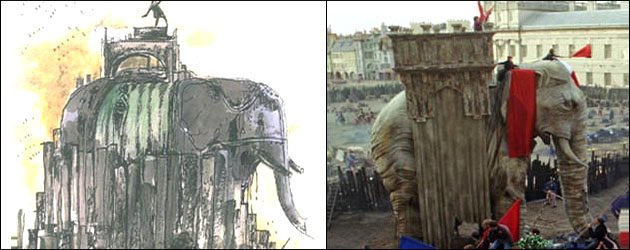

HB: A few weeks ago Variety called me about a Tweet I’d sent out about some of the film companies and how they’re handling the pandemic. My basic sentiment is the bigger the film’s budget, the easier it will be to handle. The larger the studio, the easier it is. I see the bigger movies coming back. And movies are still currently in development. That hasn’t stopped because those people work remotely- all the illustrators, concept artists, animators, set designers.