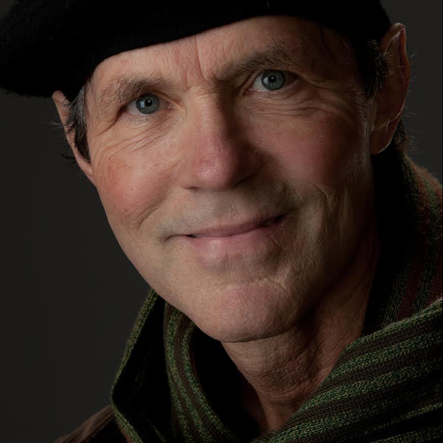

Rick Carter

Rick Carter is a legend in the field of production design. With Avatar and Star Wars VII: The Force Awakens, he designed two films that have each made over two billion in the box office. He’s spent a career teaming up with three of the greatest filmmaking visionaries who ever lived- Steven Spielberg, James Cameron and Robert Zemekis, to create such classic films as Jurassic Park, Forrest Gump, Back to the Future II and III. To date he’s won two Academy awards, one for Avatar and one for Lincoln. Most recently he designed Star Wars IX: The Rise of Skywalker. I connected to Rick in the middle of the worldwide Corona virus pandemic, with our industry on hold…

AS: Is all production and prep shut down for you because of the Covid 19 virus?

RC: It really is. There’s some prep going on but for the most part it’s shut down. People are trying to figure out when they can actually start up a production and how to do it because getting people together is not an easy task. Keeping people safe is the first and foremost thing. Secondarily, what kind of art can we create in this environment? It will have a profound impact on what movies are and how they’re made.

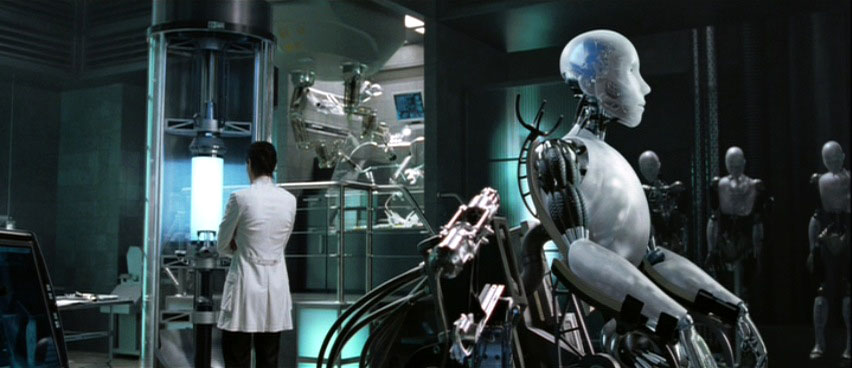

The job of production design is not going to be dependent on what we’ve had in this last epoch. Production design is not a static thing. Just the advent of computer imagery into the process caused a development that we’ve all had to adjust to, those of us who’ve been around for a while. And here comes another change and this one’s going to be very, very trying but I think it will lead to great solutions. Designers will have to really help design the production, not just what it looks like.